So you want to be a samurai, eh? When I ask people who revere the samurai “What is it about the samurai that you find so great?” The most common answer is that they are impressed by the bushido code. There is a lot of good stuff found in what is termed the bushido code. Most of it predates the bushi by 1500 years or more, and the rest was added in the early 20th century when the term “bushido” was first widely used. Most of the stuff about sacrificing oneself for one’s lord other such more extreme was only added in the early 20th century.

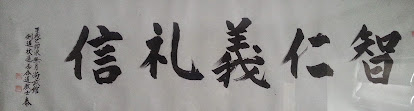

The parts of “bushido” that weren’t added by fascist military promoters in the 20th century are quite good. It's just that they are basically the 5 virtues of Confucius. I have a piece of calligraphy in my living room done by my budo teacher, Kiyama Hiroshi Shihan, that lists them in this order:

智 仁 義 礼 信

In Japanese they are read:

Chi 智 or “wisdom”.

Jin 仁 or ”benevolence”

Gi 義 or “righteousness”

Rei 禮 or “ritual propriety”

Shin 信 or “Trust”

These all seem like really good virtues, especially if you understand a little about Confucian thought. I can’t think of anyone who would argue that chi, or wisdom, is a bad thing. Developing wisdom requires having some understanding of the world, so study and learning is encouraged as a means of acquiring wisdom. This includes active, lifelong studying for self-improvement. Once you have some wisdom and understanding, you have to act on it. Wisdom without action isn’t really wisdom.

Jin, or “benevolence” can be a tougher sell for some people until they begin to understand the context. Jin includes acting in a way that makes the world better for everyone, not just for yourself. It’s not giving charity blindly. It’s actively making the world around you a better place. In some situations that may mean giving charitably. In others it may be buying a quieter lawn mower so you don’t disturb your neighbors when you cut the grass. It could be volunteering to help kids with their homework or to just give them a safe space to be kids. Take a CPR class. Begin composting. Donate blood. Take an art class and improve yourself. There are infinite possibilities for benevolent action.

Gi, or “righteousness” sometimes makes people uncomfortable because they associate righteousness with self-righteous people who already have all the answers and know exactly how everyone should behave. In this sense though, gi is about doing what is right in any situation rather than what you want or what benefits you as a person, and it has almost nothing to do with telling others how to behave. It means, and this was critical for the samurai, doing whatever you have to to fulfill your responsibilities and duties in society. This is something that is usually overlooked when talking about the samurai. The samurai were all about meeting their responsibilities. Ideas of personal rights would have been considered the ultimate in selfishness. Choosing to do the right thing has always been difficult. Confucius and the philosophers of ancient China were debating what is right and how to do right 2600 years ago. For Confucians, being righteous has always been about right action first and foremost. The samurai was expected to be quiet and demonstrate his righteousness through action.

Rei, or “ritual propriety”, in Confucius’ time could be read as literally meaning “rites” as in ritual actions. Confucius used it in that sense, but in a much broader sense as well. He was not only talking about religious rites, or formal ceremonies of state. He was also talking about the proper etiquette you have learned and should use in each situation. These are rei as well. Saying “Good morning” when you walk into the office. Shaking someone’s hand in a way that is neither trying to crush them nor just making a show of touching their hand without any sense of connection. It’s remembering to announce that you’re home so no one is surprised because they didn’t know you were home. It’s helping clean up the table after a meal instead of rushing back to your game. It’s etiquette, but more than just the formal bits. It is also seen as a means of self-cultivation. By behaving according to propriety, you learn to guide your heart/mind to propriety so that the ritual ceases to be ritual. It becomes sincere action.

Shin, or trust, is about others being able to trust you. In the dojo that means your partners can trust you to do the exercises that are being practiced that evening, and not suddenly go off and do your own thing. In kata they are confident that you will do the kata correctly so they can get the maximum benefit from the practice. You don’t overwhelm those who are less skilled, and you do your best when working with the seniors. You can be trusted to keep your word and to honor implied agreements like the agreement in the dojo that no one tries to hurt or injure anyone, that everyone helps each other to learn to the best of their abilities.

These are the real samurai values. They are at the core of nearly everything that was written and believed about how samurai should conduct themselves. The best of samurai embodied these values in how they lived. The samurai were as human as anyone else, and they had all the faults and shortcomings of humans. The more you see leaders and thinkers of the samurai writing about the value of a particular virtue, the less likely you were to find that virtue being displayed at that time. Throughout the civil wars leading up to the Tokugawa shogunate, loyalty was praised loudly. It shouldn’t be a surprise that betrayal was common. None of the Confucian virtues are easy. Virtues never are. I know I fall short of anything like being a wise, righteous, benevolent man of proper action and trust. These values are worthy goals, but they don’t belong just to the samurai. Confucian scholars began promoting them in China 2600 years ago, and the Japanese recognized their value.

Rather than just parroting the virtues, I suggest studying them a little. For an enjoyable introduction to Confucius, try Confucius Speaks. It an excellent introduction to Confucius by Taiwanese cartoonist Tsai Chih Chung. Two good places to go a little deeper are The World Of Thought In Ancient China by Benjamin Schwartz and The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About The Good Life by Michael Puett. There is also a free class you can take with Puett about this at EdX. These two cover more than just Confucius, but they both start with him. Everything else they go into was also important in any discussion of values and ethics by the samurai.

Samurai values weren’t platitudes. They weren’t (usually) jingoistic. They were values and ideas that real people struggled to understand. How should these values be manifested in the world? People struggled with living up to what they found was good and right. If you really respect the samurai and their values, find out what things they studied and study them yourself. You can do worse than by starting with what Confucius had to say.

What does all this have to do with budo? If you’re really learning any form of Japanese budo, but particularly koryu budo, these values shape everything within the budo world. Koryu budo ryuha are built on Confucian values. That’s part of why you can’t learn koryu budo without a teacher. Part of being a member of ryuha is learning the behavior that is expected and the responsibilities that go with being part of the ryuha. The techniques and kata are the physical part, but there is much more to be learned about relationships, responsibilities and right action. That is all part of koryu budo. It’s not just about how to win a fight. It’s about learning to fulfill your duties in the ryuha and society so that perhaps fighting won’t be necessary.

My thanks to Kevin Tsai, PhD. for his assistance in expressing the Confucian values accurately in understandable way. Any errors are mine.